Interface-Aware Media Design: A Civic Architecture for the Post-Truth Age

What if journalism isn’t a mirror of reality but an interface shaped by evolution, one that rewards outrage over understanding? To survive the post-truth era, media must be redesigned as civic infrastructure: transparent, deliberative, and calibrated to human perception, rather than platform logic.

Bridging Hoffman’s Interface Theory of Perception and Civic Journalism

Executive Summary

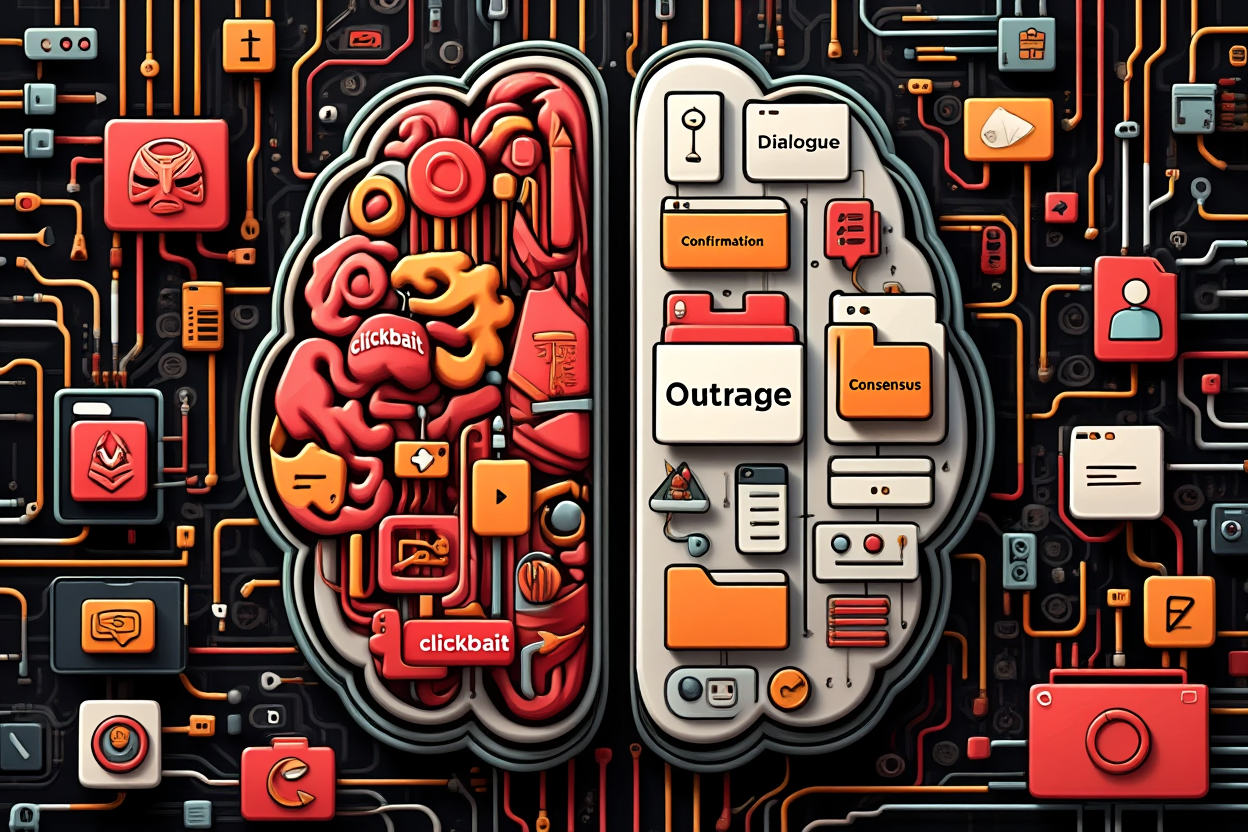

Human perception, as posited by Donald Hoffman’s Interface Theory, is not a mirror of objective reality but an evolved interface optimized for survival. In this context, digital media systems, particularly those driven by engagement algorithms, exploit perceptual shortcuts that evolved for fitness, not truth.

The result is a media ecosystem that privileges tribalism over deliberation, spectacle over substance, and virality over verification. This white paper introduces the concept of interface-aware media design as a new civic paradigm.

Drawing from Hoffman’s theory, deliberative democratic models, and working civic tech examples, we outline design strategies that treat media not as passive information delivery but as civic infrastructure calibrated to human cognition. We argue for transparency, structured deliberation, AI-powered perceptual scaffolds, and community-grounded governance as design imperatives for media in a fragmented, post-truth age.

Source Article:

Title: The Interface Theory of Perception

Author: Donald D. Hoffman, Manish Singh, and Chetan Prakash

Published in: Psychonomic Bulletin & Review, 2015

DOI: 10.3758/s13423-015-0890-8

Direct Link: https://link.springer.com/article/10.3758/s13423-015-0890-8

I. The Perceptual Challenge: Evolution vs. Truth

Donald Hoffman’s Interface Theory of Perception argues that organisms evolve to perceive not objective reality, but a useful distortion of it. Our perceptions are more like desktop icons than windows—symbolic simplifications that allow us to act effectively, not understand accurately.

Implications for Media

- Fitness-Over-Truth Bias

Evolution favors heuristics that enhance survival and social cohesion, such as confirmation bias, tribal signaling, and emotional salience, rather than epistemic accuracy. These instincts, exploited by engagement-optimized platforms, lead to the amplification of outrage, identity reinforcement, and epistemic fragmentation. - The “Stubby Bottle” Problem

As jewel beetles once mistook beer bottles for mates, humans mistake trending content for significance. Sensationalism and algorithmically boosted content hijack our evolved attention, marginalizing nuance and reducing journalism to reactive spectacle. - Collapse of Shared Reality

When journalism assumes perception is a transparent lens rather than an evolved interface, it fails to account for the various inherently human distortions. Instead of correcting for perceptual bias, many outlets inadvertently accelerate it, further contributing to epistemic silos and the breakdown in shared civic understanding.

II. Principles for Interface-Aware Design

We propose four design pillars to re-engineer journalism as civic architecture—a scaffolding that accounts for inherent human cognitive limitations while facilitating democratic participation.

1. Explicit Framing and Transparency

- Narrative Context Labels

Every story is a frame. Labeling articles with perspective indicators—e.g., "This piece was shaped by three journalists living and working in New York City, with training from institutions like NYU and Columbia. Our close proximity to legacy media, urban Northeast U.S. politics, and academic discourse on democracy and design informs our perspective; we name that here not to claim authority. But, in our work, we acknowledge that every frame reflects a vantage point and in doing so, we advance this transparency, which is a part of what civic trust requires, and we hope that others who read this will do the same." - Dynamic AI Metadata

Content could be accompanied by metadata such as “This moral claim conflicts with X studies” or “This policy proposal is favored by Y demographic and the moral groups who favor X.” These contextual overlays act as perception-corrective tools.

Cognitive Rationale:

Hoffman’s metaphor of the desktop icon clarifies that perception is symbolic, not literal. Making journalistic frames visible reframes media as interfaces rather than supposed mirrors of truth.

2. Structured Deliberation Architectures

- Civic Squares Modeled on PubHubs

Online discussions should mimic democratic procedures by utilizing moderated forums, presenting side-by-side arguments, rotating moderators, and incorporating timed reflection periods; design matters, not just of content, but of the service itself. A well-structured civic discussion space requires thoughtful orchestration of touchpoints, roles, and backstage systems that support trust, inclusion, and usability. - Civic Value Metrics

Traditional metrics (clicks, likes) reinforce tribalism. Replace them with Pluralism Scores (range of viewpoints) or Constructive Discourse Indices (evidence of problem-solving, listening).

A service design approach treats metrics as part of the civic experience, not just a hidden backend measure. By replacing vanity metrics with Civic Value Metrics—such as a Pluralism Score (which tracks the range and diversity of viewpoints presented) or a Constructive Discourse Index (which measures evidence of listening, synthesis, and solution-oriented dialogue)—newsrooms create feedback loops that shape both user behavior and editorial choices.

Frontstage: Readers and participants see indicators of discourse quality alongside content, making pluralism and constructive exchange visible and rewarding.

Backstage: Editorial teams and moderators have tools to monitor and improve these metrics, using them to adjust facilitation, diversify sourcing, and ensure that the “service” of journalism sustains a healthy civic space.

Why it works: Service design makes these metrics not just performance indicators but design elements—embedding them into every touchpoint and workflow so that the entire experience reinforces civic goals, not just engagement triggers.

Cognitive Rationale:

Perceptual biases evolved for small-group cohesion. Civic design can stretch our “cognitive coalitions” by engineering exposure to opposing views within psychologically safe frameworks.

3. AI as Perceptual Prosthetics

- Omission Alerts

Algorithmic tools can identify silences: “Rural perspectives missing,” “No youth or elder voices included.” The absences become the signal that carries the logic. - Neutral Summarization

LLMs and other AI systems can distill debates into neutral, synthesis-oriented overviews—acting as perceptual aids rather than engagement bait.

Cognitive Rationale:

Since human perception is selective and limited, AI can serve as a prosthetic that extends our epistemic reach—if designed not to amplify bias but to counteract it.

4. Community-Driven Calibration

- Co-Creation Networks

Programs like City Bureau’s Documenters train citizens to record public meetings, turning civic witnessing into structured, compensatory labor. - Deep Listening Protocols

Interfaces should evolve based on continuous community feedback, creating a dynamic, reciprocal loop between media producers and the publics they serve.

Cognitive Rationale:

By grounding design in local experience and collective cognition, we counteract the alienation and top-down control that often characterize platform-driven media.

III. Case Studies: Civic Interfaces in Practice

City Bureau’s Documenters Program

Approach: Trains and compensates local residents to document municipal governance.

Interface Design: Live annotation, contextual fact-checking, and participatory data collection.

Outcomes:

- 87% of users reported increased trust in local journalism

- 63% engaged in civic actions post-participation

Netherlands’ PubHubs Project

Approach: Public-interest digital spaces with local moderation and transparency by design.

Interface Design: Identity-safe spaces, civic moderation rules, semantic content tagging.

Outcomes:

- 42% reduction in toxic discourse

- Statistically significant increase in cross-partisan engagement

IV. Implementation Roadmap

For Newsrooms

- Bias Audits: Analyze how design (headlines, imagery, comment systems) triggers fitness heuristics.

- Prototype Civic Hubs: Partner with organizations like Hearken or GroundSource to test deliberative models.

- Metric Shift: Replace engagement scores with Civic-Value indices to track pluralism and trust.

For Platforms

- Fitness Transparency: Require public disclosure of algorithmic priorities and their civic implications.

- Revenue-Sharing: Redirect a portion of ad revenue to fund co-creation initiatives like Documenters.

- Design Nudges: Introduce deliberation-promoting friction—e.g., prompts to view opposing views before sharing.

For Funders

- Tool Prioritization: Invest in tools that detect omission, summarize neutrally, and facilitate co-creation.

- Mandate Equity Reporting: Require transparency in demographics and processes from grantees and tech partners.

- Sustainability Grants: Shift from one-year pilots to multi-year investments in interface transformation.

V. Conclusion: A New Perceptual Contract

The media is not failing because it lacks information. It is failing because it misunderstands perception. If Hoffman is right, journalism must abandon the myth that it reflects reality and instead design for how humans actually see, decide, and engage. That means not just telling the truth, but shaping the interface through which truth becomes actionable.

In the post-truth age, journalism must become a civic architecture—a system of scaffolds, filters, and deliberative paths that enable diverse publics to interact with complex reality. Transparency, deliberation, AI scaffolding, and community co-creation are not just design options; they are democratic imperatives.

As Hoffman warns, perceptions that ignore fitness go extinct. However, in civic life, the inverse is also true: interfaces that disregard the coherence of meaning required by pluralistic societies can undermine democracy itself. The American political experiment was never designed around epistemic consensus—it was, from the outset, a federation of difference. Our constitutional architecture protects dissent and decentralizes power precisely because it assumes that truth, experience, and identity will diverge.

As John Dewey argued, democracy is not merely a system of governance but a mode of associated living, where meaning must be continuously reconstructed through public communication. For Dewey, the press was not a mirror but a mechanism—a way to make disparate experiences intelligible to each other.

Yet in today’s media ecology, that shared intelligibility is breaking down. What Hannah Arendt called “the common world”, the space between people where facts are negotiated and made durable, is dissolving under the weight of algorithmic personalization and performative outrage.

Without shared structures of appearance, Arendt warned, public life collapses into loneliness, where propaganda takes the place of truth and spectacle overwhelms judgment. Meanwhile, Rawls’s vision of a well-ordered society, one in which reasonable pluralism is made coherent through fair deliberation and justified public reason, depends on media systems capable of structuring disagreement without succumbing to faction.

Journalism, in this light, must be reimagined as a civic interface—not a conveyor of objective facts, but a design system that scaffolds shared meaning across difference. Today’s media platforms, shaped by market incentives and evolutionary triggers, are designed for the opposite. They reward tribal instincts and attention economies rather than coherence and deliberation.

In the post-truth age, journalism must evolve, not toward futile neutrality, but toward an interface-aware architecture that is attuned to how humans perceive, and that is committed to the democratic imperative of holding a world in common.

Citations

Al-Zboon, M. S. (2023). The effect of design on perception of media content. International Journal of Media and Communication Studies, 15(1), 22–38.

Arendt, H. (1958). The human condition. University of Chicago Press.

City Bureau. (2022). Documenters impact report. Retrieved from https://www.citybureau.org/documenters

Dewey, J. (1927). The public and its problems. Henry Holt and Company.

Hoffman, D. D., Singh, M., & Prakash, C. (2015). The interface theory of perception. Psychonomic Bulletin & Review, 22(6), 1480–1506. https://doi.org/10.3758/s13423-015-0890-8

Hoffman, D. D. (2019). Perception: Why it evolved, and what it’s for. In J. T. Wixted (Ed.), Stevens' Handbook of Experimental Psychology and Cognitive Neuroscience (4th ed.). Wiley.

Hoffman, D. D. (2024, October). Perception, evolution, and the explanatory scope of scientific realism [Open access]. Imprint. https://www.imprint.co.uk/wp-content/uploads/2024/10/Hoffman_Open_Access.pdf

Journalism That Matters. (2017). Journalism for democracy and communities. Retrieved from https://journalismthatmatters.org/

PubHubs Project. (2024). Public digital infrastructure in the Netherlands: A values-driven approach to civic discourse online. Retrieved from https://www.pubhubs.net/

Rawls, J. (1993). Political liberalism. Columbia University Press.