Restoring Meaning in an Age of Distrust in News as Relates to Politics

Journalism is failing not from bias alone, but from a deeper unwillingness to confront its own epistemological and cultural blind spots.

As America confronts deepening political polarization and an ever-accelerating news cycle, trust in the press has eroded. This is not merely due to partisanship or social media chaos, but because journalism itself has failed to update its self-understanding for the 21st century.

Rooted in Enlightenment ideals of objectivity and rational discourse, journalism has struggled to adapt to a postmodern context where truth is contested, authority is fragmented, and the public is disillusioned. The crisis is not simply external. It stems from an intellectual monoculture in legacy newsrooms that mistakes its own worldview for neutrality, marginalizing broad swaths of the American experience in the process.

The illusion of objectivity has become a liability. In an age when citizens are at risk of becoming unmoored from purpose, the loss of faith in the coherence of meaning creates a vacuum—one that easily gives way to nihilism, psychologically, culturally, and politically.

This epistemological rupture in journalism is mirrored by the decline of other meaning-making institutions such as religion, education, and civic life, leaving the public not just uninformed but atomized. What is needed is not more content or louder punditry but journalism that honestly acknowledges the effect of epistemological pluralism on divergent notions of “truth” and advances a new kind of transparency and journalistic humility.

Artificial intelligence, used thoughtfully, can assist in this transition. It can enhance investigative and contextual depth, detect biases, and highlight the role of rhetorical narratives across discourses within political communities. However, no algorithm can substitute for moral courage.

Journalism must reclaim its public mission. Its role is not to stand apart from society, pretending to be “objective” and offering neutral detachment, but to stand within it, uncomfortably– because we all have to stand somewhere.

The goal is to be unafraid to confront both power while also holding the humility to understand the inherent blind spots in the system of journalism itself—this requires reflexivity. Only then can journalism begin to restore the discourse and language of shared meaning upon which American democracy depends.

“Who can we trust anymore?”

This weary question, tossed around dinner tables and comment sections, reflects more than public frustration; it signals a moment of American civic rupture; it is a collapse of confidence and also of shared meaning. The institutions that were once charged with holding our public trust have faltered, and perhaps none more visibly than the press.

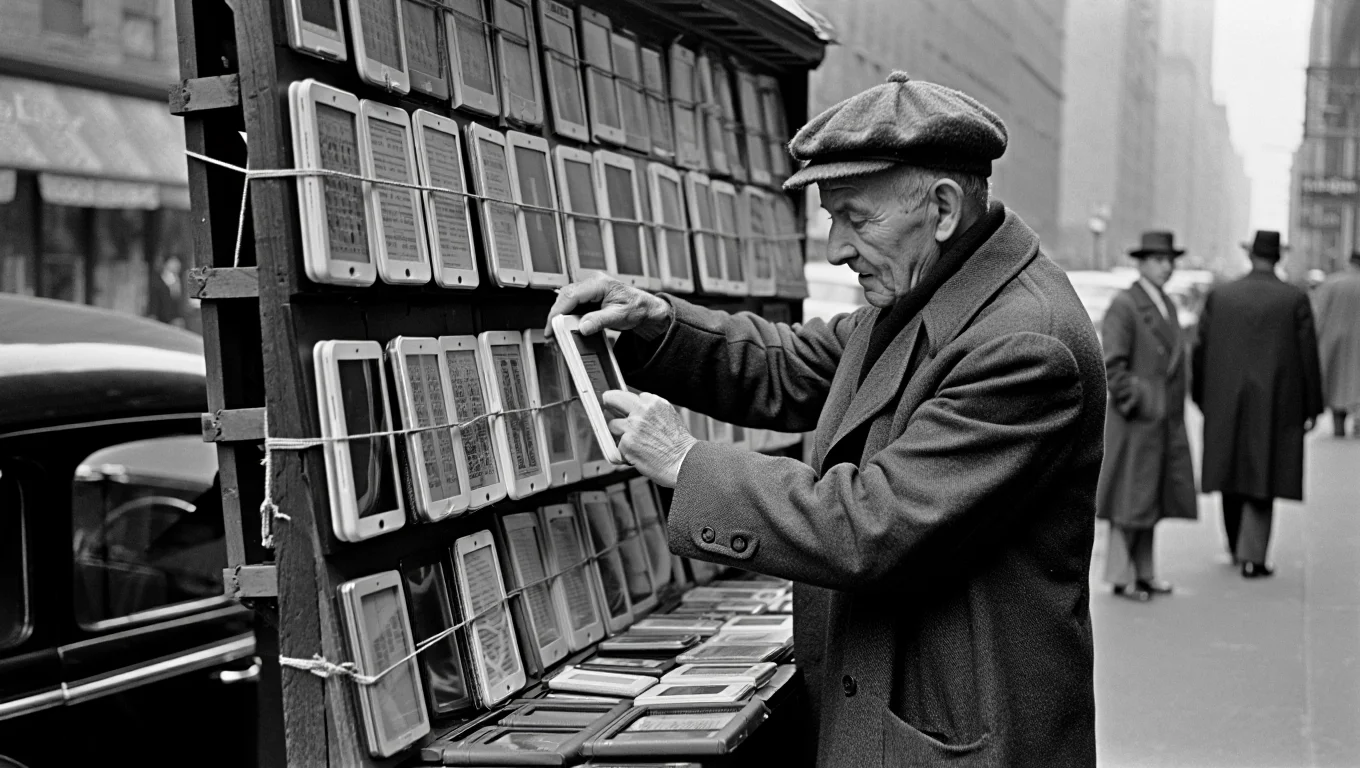

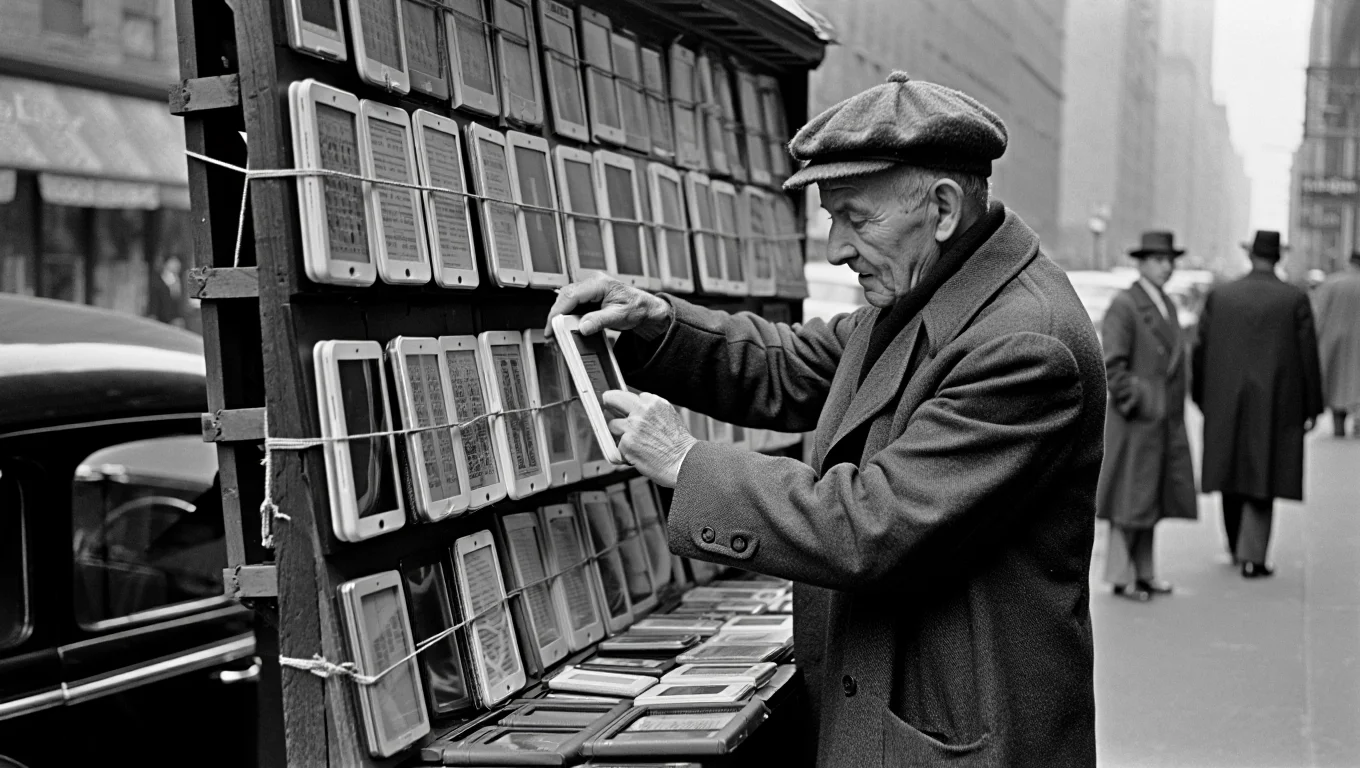

At the heart of this disintegration lies not only the decline of principled print journalism, as the Law & Liberty essay “Can We Restore American Print Journalism?” underscores, but also a broader erosion of trust in media. While the essay focuses primarily on the collapse of traditional formats and the challenges of preserving journalistic integrity in a digital age, the deeper crisis extends beyond the infrastructure. It includes journalism’s struggle to interrogate its own assumptions, especially the persistent belief in objectivity amid increasingly ideological internal cultures.

This connects to a courageous point made by New York Times opinion columnist Bret Stephens during the Good Night and Good Luck panel discussion on CNN, June 7, 2025. Stephens, a Pulitzer Prize–winning conservative voice within liberal media, argued that the deeper threat to truth today is not overt partisanship, such as that found on Fox News or MSNBC, where biases are at least explicit. Rather, it lies in the ideological uniformity of legacy newsrooms that continue to present themselves as neutral.

According to Stephens, the press’s gravest distortion is not in what it reports, but in what it fails to perceive—its blind spots. To extend his critique: this failure reflects not just intellectual monoculture, but also a lack of institutional reflexivity.

At its core, this is a philosophical failure as much as a professional one. Journalism has yet to come to terms with the postmodern condition—the collapse of epistemic certainty and the contestation of truth itself. Instead, it remains tethered to a romanticized, 20th-century conception of objectivity that no longer holds under scrutiny.

The field’s practices still operate as if facts speak for themselves, without acknowledging how framing, power, and narrative construction shape perception. In doing so, journalism not only misreads its audience but also misses the opportunity to lead with honesty about its epistemological limitations.

Reporters and editors, shaped by overlapping cultural and ideological milieus, often misread or overlook the realities of the nation they report on. Communities such as Trump voters, religious conservatives, and the working poor are not merely underrepresented—they are rendered opaque, their complexity reduced to assumptions about static "interests."

The issue is not bad faith but a form of professional myopia, amplified by the structural limits of human cognition and cultural proximity. Journalism, caught in an echo chamber of its own making, risks mistaking internal consensus for national understanding.

This failure echoes Edward R. Murrow’s seminal confrontation with Senator McCarthy in 1954 on See It Now. Quoting Shakespeare, Murrow warned, “The fault, dear Brutus, is not in our stars, but in ourselves.”

But he didn’t stop there. With remarkable moral clarity, he added, “The terror is right here in this room.” Murrow was not simply challenging McCarthy’s abuses—he was calling the press to account for its complicity, its silence, and its fear. That same challenge remains urgent today. Journalism must not only interrogate power but also its own institutional habits, assumptions, and blind spots. The fear Murrow named still lingers—not in far-off offices of government, but in editorial rooms unwilling to confront the inherent narrowness of the lens itself.

That confrontation, dramatized in George Clooney’s recent Broadway production of Good Night and Good Luck, remains just as urgent today. Journalism must stop looking away when challenged about its complicity. It must reckon with the contradiction between its claimed “objectivity” and the perspectives it cultivates.

Unlike partisanship, which declares its commitments openly, ideological homogeneity cloaked in claims of neutrality presents itself as a “view from nowhere”—a posture that, as Bret Stephens rightly observes, often excludes more than it includes. This is not merely a professional lapse; it represents an epistemological crisis.

Contemporary journalism, still tethered to its 20th-century ontogeny, has yet to reckon fully with the insights of postmodernism. It continues to rely on a romantic legacy of objectivity that fails to recognize how knowledge is always situated—how reporting inevitably reflects the cultural assumptions and power relations of those who produce it.

This challenge has deep intellectual roots. From Marx’s recognition of ideology and class consciousness to the standpoint theories of feminist scholars like Nancy Hartsock and Sandra Harding, the idea that perspective shapes knowledge has long been in circulation. Thinkers such as Foucault and Lyotard advanced this further by questioning the neutrality of power and the legitimacy of grand narratives.

Donna Haraway’s articulation of “situated knowledge” sharpens this critique, particularly in relation to science and technology, rejecting the illusion of omniscient objectivity in favor of accountable, partial perspectives. In this light, journalism’s inherited ideal of detached objectivity appears less as a neutral method and more as an unexamined ideology itself, ultimately, blissfully blind to the material, social, and cultural contexts in which the news is produced.

What’s needed now is not the rejection of truth-seeking and facts, but a renewal through reflexivity, intellectual humility, and transparency. Journalism must reckon with its role not only as a conveyor of “fact” but as a constructor of meaning, not universal truth, and it must remain responsible for both what it amplifies and what it renders invisible in the process.

How do we restore trust?

Other voices on the CNN panel offered familiar remedies. Kara Swisher emphasized innovation and audience-building in the fragmented digital landscape. Jorge Ramos argued for more training and fact-checking. Abby Phillip acknowledged the diversity gap but emphasized the legacy media’s resources. Connie Chung defended the ideal of objectivity, asserting that personal bias can be bracketed and managed.

Stephens wasn’t rejecting professionalism or facts; he was calling for honesty about institutional culture and this feels like a challenge that the CNN panel was reluctant to confront. In the end, journalism cannot fulfill its democratic role if it remains incurious about its own lens and unwilling to examine itself.

This matters because the collapse of journalism mirrors the broader unraveling of America’s meaning-making institutions—religion, education, and civic life. As Robert Nisbet warned, and Robert Putnam later documented, when these mediating structures weaken, individuals become more vulnerable to isolation, disinformation, and despair. In that vacuum, conspiracy and corrosive cynicism take root.

When shared truths erode, nihilism becomes ambient—this is the unspoken mood of a fracture. Among young men in particular, this psychological void can metastasize into violence. So, as a Nation, the most urgent social risk we face isn’t just polarization or misinformation; it’s the steady erosion of collective meaning itself.

Right now, we are a fractured Nation, and nihilism is a tacit risk— we must find our way out of the abyss.

Americans are not hungry for more content. They are hungry for coherence; the illusion of objectivity does not help matters– it does not resonate with where we are as a culture.

America is a fractured Republic.

American journalism, particularly political reporting and the news, as it relates to political, social, and cultural issues, must embrace a new kind of intellectual humility and integrity, grounded in an honest awareness of its inherent limitations. This is the first step toward restoring public discourse and rebuilding our shared understanding of the moral architecture of American “knowing” through the medium of cable news.

That means hiring with an eye toward intellectual humility and cultural heterodoxy, not just demographic diversity. Above all, it means breaking with the pretense that journalism can ever be purely objective. It cannot, but it can be honest, strive to be fair, and be morally courageous.

In 1954, Murrow helped turn the tide not by remaining neutral, but by standing in judgment, not of people, but of method, motive, and meaning. The same moral courage is needed now.

As Good Night and Good Luck reminds us, journalism is never just reporting the facts—it has to stand somewhere. Rebuilding cable news journalism won’t solve every crisis, but without a press that’s willing to look at itself as critically as it looks at others, we risk losing more than trust.