The Libertarian Laboratory: What Grand Theft Auto Proves About Nozick’s Minimal State

This essay argues that Grand Theft Auto functions as a virtual test of Robert Nozick’s minimal state theory. What begins as chaotic anarchy evolves into self-organizing protection rackets, mirroring how Nozick predicted real states emerge from pure negative freedom.

by Dennis Stevens, Ed.D.

I saw it immediately, the tattered copy of Atlas Shrugged resting beside his PlayStation. And, the minute that Grand Theft Auto flickered to life on the screen, I felt as if I was offered a private viewing of a metaphysical libertarian's utopian paradise.

Then, I thought maybe there's something to learn here if we look closely?

Lawlessness. Every person for themselves. This unfettered freedom feels like the ideal of negative liberty-- freedom from interference (see Berlin, 1969).

But here’s what makes this virtual world more than just digital chaos, it demonstrates what Robert Nozick (1974) predicted: that even when people start with total freedom, they tend to rebuild protective associations that function like a minimal state.

Of course, there are clarifications and caveats. Nozick’s version stops at basic protection; it doesn’t guarantee fairness for everyone.

That’s where John Rawls (1971) comes in, reminding us that freedom without fairness is often hollow. Real justice, he argued, requires structures that make sure even the least advantaged benefit. In video games, this tension plays out every time players test how much freedom they’ll trade for security, and who gets left out when they do.

Fiction like this offers a lens to grasp the more profound disagreements that shape real-world politics: how much freedom, how much fairness, and who pays the price when we get the balance wrong?

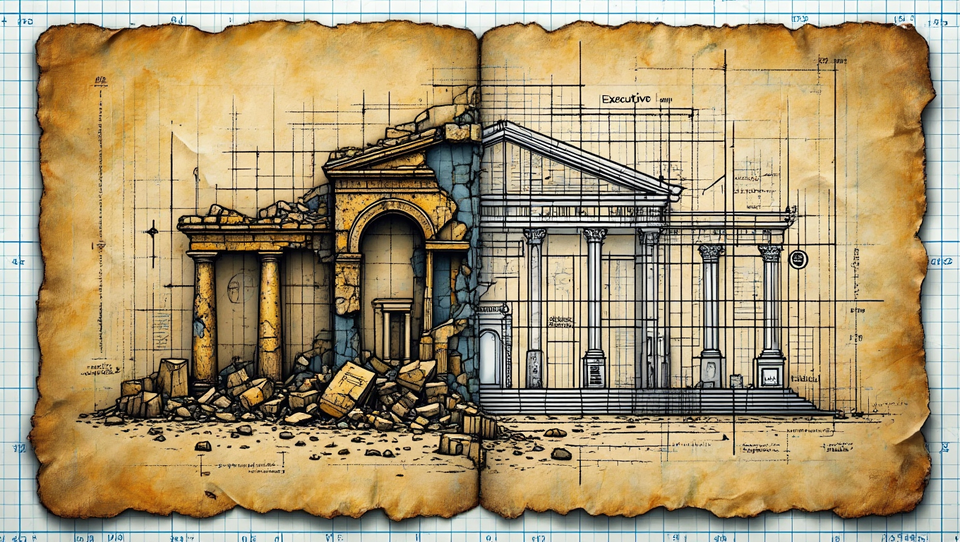

A Libertarian Laboratory

Nozick argued in his National Book Award winning "Anarchy, State, and Utopia" that anarcho-capitalism would inevitably transform into a minimal state. Not through government force, but through natural human behavior.

People would band together for protection. These protection associations would compete. Eventually, one would dominate each territory.

The result? In Nozick's conception, a minimal "night watchman" state emerges organically from pure anarchy, and most political theorists dismissed this as a libertarian fantasy. How could we possibly test such a theory?

Enter, Grand Theft Auto.

Criminal hierarchies as political proof

In Grand Theft Auto, the open world lets players run wild at first — stealing cars, picking fights, and causing chaos. But in multiplayer and emergent gameplay, you quickly see self-organization: crews form, turf is claimed, and protection rackets emerge. This mirrors what Nozick suggested about minimal states forming out of self-interest and protection.

That said, the GTA storylines themselves rarely end with stable “mini-states.” They’re tragedies about betrayal and downfall. Criminal empires rise and fall fast. So, while the game world supports the idea that humans gravitate toward protective associations, the scripted stories remind us how fragile and violent these hierarchies can be when legitimacy and sovereignty are absent.

Purchase the Rubric & Audio Here

Virtual worlds as ethical laboratories

Video games act as “ethical laboratories,” spaces where players can enact their moral and political choices rather than just observe them (Sicart, 2009). But to keep it honest: GTA doesn’t simulate a functioning state. It simulates the tension between individual freedom and gang control. The state in the background is assumed to be ineffectual or corrupt, and this world never stabilizes.

Mad Max: from tribe to lone wolf

As a contrasting example, the original Mad Max (1979) shows a civilization unraveling into warlord rule and scavenger tribes; it’s a raw vision of anarchy. But Max’s arc is not about building or joining a hierarchy; his narrative is about losing faith in all collective order. He becomes a drifter, driven by revenge and grief — PTSD in motion.

MAD MAX (1980), Official Trailer

In Mad Max 2: The Road Warrior (1981), that same world has tipped fully into desert wasteland and oil wars, but here the contrast sharpens: Max remains the loner, yet he’s drawn into a small community’s desperate attempt to preserve a shred of civilization. The setting pits anarchy (the raiders) against fragile, makeshift order (the oil refinery commune).

Max helps them, but only begrudgingly and on his terms; his narrative arc brushes up against the idea of rebuilding collective trust, only to reject it again. He escapes hierarchy, even as the world around him tries to claw some order from chaos.

The Road Warrior (Mad Max 2), 1981

Examined together, both films dramatize the tension between anarchy and the struggle for order, but Max himself remains an outlier – the archetypal barbarian nomad. Max is a character who exposes how thin and brittle social contracts are when survival is the only law.

Blade Runner: fractured authority, personal rebellion

Blade Runner (1982), offers a dystopian version of Los Angeles in November 2019, shows a world where mega-corporations overshadow state power. Policing is more like contract bounty hunting than state law enforcement, so the backdrop is a fractured authority structure. In this case, Deckard’s journey is inward; for him, it’s about an inner moral ambiguity, the ethics of hunting sentient beings, and what makes life worth preserving. He never aligns with or builds in collaboration with any protective order.

Blade Runner (1982), Official Trailer

In our final example, by way of comparison and contrast, Blade Runner 2049 extends the bleak world of the original Blade Runner, set in 2019; 30 years later.

By then, corporate power has been consolidated, and Wallace Corporation is more powerful than any government. But again, K’s story is about reclaiming personal agency in a dehumanized system, not about stabilizing or enforcing it. The film critiques how power structures grind people down rather than showing them as natural or desirable.

Blade Runner (2049), Official Trailer

The real lesson: What is the cost of order?

So what do these worlds actually say? The pattern holds for the settings: anarchic or fragmented conditions do tend to produce protective associations, whether gangs, tribes, or corporations that monopolize force. But the characters don’t celebrate or justify these new orders. They reveal how costly and morally compromised they are. Mad Max flees it. Deckard walks away from it. K dies outside it. In GTA, betrayal is constant. Choose your poison.

If there’s a takeaway that’s true to these narrative arcs, it’s this: human nature may drive us toward governance and hierarchy or away from it; these capacities exist within us. And, socially as well as culturally, among humans in a society, the legitimacy of (and the project of justice within) those structures is always in question. These stories show us the cycle and the price of our various "freedoms".

Based on broader persuasive arguments in the public sphere, we often assume that negative freedom, freedom from interference, is the only safe bet– but that is a persuasive argument; pushed to its extreme, it can turn authoritarian too. Unchecked negative freedom can become its own kind of tyranny.

When no one steps in, power can concentrate in the hands of the few who control resources, leaving the vulnerable unprotected. Private tyrannies flourish behind the veil of “hands-off” governance. Even the minimalist state can turn into a night watchman that defends privilege while everyone else is left outside the gates.

Both negative and positive liberty risk drifting into authoritarianism when taken to their extremes. That’s why the balance we aim for in civil society, the practical, imperfect middle ground, is called ordered liberty.

Beyond Entertainment

Modern gaming spaces act as experimental grounds where people test different ways of organizing and interacting to pursue goals within a simulated world of resources (Castronova, 2005). Some researchers have even suggested that the governance structures tested in virtual worlds today may foreshadow the political systems we build tomorrow.

Virtual worlds allow us to observe political theory in action without the ethical constraints of real-world experimentation.

When millions of players independently create similar organizational structures across different game servers, we're seeing something more significant than entertainment. We're witnessing repeated validation of fundamental political theories.

The Limitations of Virtual Politics

GTA as a political model has obvious limitations. Players can respawn after death. Virtual property has no real scarcity. The consequences of violence are temporary.

But these limitations actually strengthen the case for Nozick's theory. If protective associations emerge even when the need for protection is artificial, how much stronger would this tendency be in the real world, where death is permanent and property genuinely scarce?

The game strips away the moral and practical complexities that obscure political theory in real life. What remains is the bare skeleton of human organizational behavior.

Cultural Artifacts as Demonstrative of a Political "Truth"?

Atlas Shrugged and Grand Theft Auto represent the same libertarian impulse expressed through different media. Both imagine worlds where individual freedom operates without external constraint.

Both ultimately demonstrate that pure individualism is unstable.

Characters in Rand's novel form companies and alliances. Players in GTA form gangs and territories. The cultural artifacts we create reveal truths about political behavior that academic theory pedantically alludes to; these virtual worlds, the dystopian fiction, and other forms of interactive media serve as testing grounds for ideas that would be impossible or unethical to implement in reality.

Nozick’s minimal state finds its most vivid test not in the lecture hall but in millions of players who recreate his prediction every time they log into a digital world. The PlayStation and Atlas Shrugged belong on the same shelf.

But, like it or not, we have to build governments, even in paradise; the real world can be cruel, and video games are a fun distraction from a more complex reality.

Bibliography

Berlin, I. (1969). Two concepts of liberty. In I. Berlin, Four essays on liberty (pp. 118–172). Oxford, UK: Oxford University Press.

Castronova, E. (2005). Synthetic worlds: The business and culture of online games. Chicago, IL: University of Chicago Press.

Nozick, R. (1974). Anarchy, state, and utopia. New York, NY: Basic Books.

Rawls, J. (1971). A theory of justice. Cambridge, MA: Belknap Press of Harvard University Press.

Sicart, M. (2009). The ethics of computer games. Cambridge, MA: MIT Press.

Purchase the Rubric & Audio Here